Exercising the art of scoring to film is a difficult task, as a lot of diffrent aspects influence the outcome of a piece or how easy it is to accomplish the task. While obvious exercises like “write music every day” or “listen to music” are surely not bad to begin with, I like to give you a more practical-orientated view.

The goal of a practice score is to open up your horizon for a new use of the orchestra, more advanced structures and orchestration techniques, as well as fasten up your scoring process. Therefore the practicing methods vary on the subject you want to improve on, and for each aspect, diffrent approaches work better than others. Breaking habits, experimenting with new sounds and focusing on advanced scoring techniques are among the fundamentals.

But before we dive into all the nitty details, let’s take a look at a few general aspects of scoring exercises:

WHAT ARE THE GOALS OF SCORING EXERCISES?

Especially in the beginning phase of your orchestral journey, many hurdles are to overcome as your skillset and experience just start to grow. It is therefore a mistake to assume you can learn everything from the get-go. Exercises, or practice studies, if you like the term more, are a fundamental approach to strengthening your foundations and learning new techniques as well as growing your musical horizon. But what are the most crucial aspects a practice session should focus on?

Generally said they can be categorized into three main groups:

New Soundscapes

At a certain point, usually, after you manage to write your first few tracks, you might run into a barrier where you repeat the same sound structure over and over with the impressions, that that’s the only way it works. Every instrument follows the same route and every melody is built the same way. It was pretty hard for me to step out of this tendency and get lose of this habit. It is therefore crucial to understand the diffrent tonal colors of the orchestra and how to combine them to a more fitting end result.

More advanced orchestration methods

Using a 4-chord structure with the same repeating chords over and over is initially a good way to get the thing rolling. But once you start to understand the orchestral music itself better and better it is time to implement more advanced structural details. Substituted chords, uneven chord structures, time changes, or counterpoints are excellent ways to transform a solid score into a fascinating piece of art. They aren’t necessary all the time, but the knowledge of such things widely improves your possibilities for your next cue.

Easier and faster workflow

Apart from the technical requirements like getting familiar with your software, the goal should be to transform the sound you imagine in your head into a mockup as quickly as possible. A lot of the time we restrict ourselves to pure improvisation, as we try to find ideas when simply pressing the keys on the midi controller. But aside from this, writing down the melody or orchestral sound you have in your head is crucial. This not only makes it easier to come up with ideas, but it also tremendously fastens up your working speed.

WHY SHOULD YOU EXERCISE INSTEAD OF WRITING A FINISHED POLISHED TRACK?

Bringing your scores to an end is undoubtedly a significant advantage for a few reasons: You go throughout the entire process and get knowledge of every state of the work, be it improvising, orchestration, or mixing. You also have a finished track you can show people and be proud of what you achieved.

On the other hand, writing one track after another without trying to bring in new aspects will result in a similar result each time, and you get stuck. Sometimes it results in a writer’s block, as you feel you’re doing the same over and over and you’re at the end of your ideas for this approach.

A pure exercising cue on the other hand has the benefit, that it doesn’t need to be shown to anybody. You focus on a single aspect you want to improve on and try your best, not without the fear of having a less quality sounding result.

Another significant benefit is time. I personally need around 70-100 hours for a finished track, which is a massive time consumption. A practice cue on the other hand, can be rushed out on a lazy afternoon. This combines a writing routine with the benefit of learning a few new bits here and there and not letting you burn out over the same chords over and over.

WHAT ARE SOME GOOD EXERCISES FOR ORCHESTRATION?

The orchestration is surely one of the most complex but rewarding aspects of writing music, be it for film or standalone. The focus of your practice should follow your current skillset. Harmony and countermelody structures are a good start if you are an absolute beginner. For more advanced composers, modular interchanges, counterpoints, or the implementation of passing chords might be an exciting aspect to dive into. For a more practical approach, I suggest the following points:

1. Breaking Habits

Apart from the already discussed habit of repeating specific structures, muscle memory and a repeating style of instrumentation are common commodities in beginner scores. Instead of reusing the same chords over and over, the table of chords I showed in this post to write individual chord progressions, is a good help.

For instrumentation, I like to compare how diffrent composers implement the Tuba for example. Most use it as a second string bass, to slightly modify the tonal color of the bassline. Other composers use the tuba as a trombone, while Sibelius used it as a French Horn (!). Using an instrument to such an extent leads you to new nuances of orchestral color and has a huge impact on its timbre. This also forces you into detailed articulation, as you need to adapt all the possibilities an instrument offers in order to fulfill such a task. To enforce this even further, you might consider writing a solo cue for one instrument in specific.

2. Recreation of Sound

A score study can be done by either going through the sheet music or recreating the desired sound by ear. I found this to be an enormity beneficial task, to either get in the mood of a new composition in this genre or if you have heard a sound cluster you want to recreate. Especially in modern-day cinema music, where many digital sounds are prominent, we can’t recreate them by looking at the sheet music only.

I have completed this exercise with two tracks so far, and it’s actually not as challenging as you might think initially. It’s enough to get the proper chords and melody line right on the piano, as the rest usually is just an orchestration process from this piano line. If you struggle with playing music by ear, you can always look up sheet music or one of the various piano tutorials on YouTube.

The significant benefit of this exercise is that you open up your horizon in terms of orchestration. It’s a similar approach to observation and study as shown above, but it has a much more practical and in-depth focus. If you want, you can check this article, where I recreated a small part of the Inception Theme “Time” by Hans Zimmer, to show the process of chord voicing.

In this exercise I started by looking up the chords for this cue and recreated the sound as good as I could. If you want to take a look at the entire process, take a look at this post: The basis for every good orchestration – Chord Voicing explained by the example of Inception

Another brilliant point of this method is that you are not distracted by the composing process of finding melodies. Writing music daily surely is a good habit, but to be real: Comming up with original ideas every day is a tough task at the beginning. To finish a track takes even more time. So with this technique, you can set up your DAW and start right away with a solid orchestration practice.

3. Short vs. Long Motifs

At the beginning of my studies, I stuck with short 4-bar melodies. It felt natural and logical, but not because I chose to do so. Nowadays, I try to extend my ideas to at least 8 bars before starting with variations. This results in a more complex structure and a more diverse experience for the listener. Along the way, many opportunities arise to use bits as a second motif or counterpoint, which makes the further process even more exciting and easier for you as a composer, as you have a lot more open leads at your hand.

4. Counterpoints

I like to use the words of John Rahn here to describe the concept of a counterpoint:

Generally said, more than one melody line smashed together builds up the cue. This was a fundamental technique used in the classical works of Bach, Mozart or Beethoven, giving them the classic Baroque vibe. Even though this isn’t a common practice nowadays, it is worth trying out. This lets you create a musical potpourri with several diffrent lines, which, in the long run, are beneficial in terms of writing countermelodies, advanced harmonic structures, and interesting rhythmic companies. In cinema film music, John Williams was a master of this technique, as he often used this method to make a cohesive sound. Here is a good example example:

Starting from 0:56 we can clearly hear many melody lines being combined to a cue increasing in tension over it’s duration. Even the countermelody itself, played by the trumpets, has a second answer call from the mallets, so the counterpoint melody creates a full bed, on which “the force theme” can lay.

WHAT ARE SOME GOOD EXERCISES FOR FILM SCORING?

Apart from pure composition, Film Music always has a story, an emotion, or an ambient to carry in its performance. Of course, you can use practice footage or participate in scoring competitions, which are a really great opportunity, but those are long sessions that aren’t the focus of this post here. If you want more information on where to find practice footage, I recommend this post here: Scoring to Film – Where to get movie footage

But for now, what are short afternoon exercises to get better at depicting the screenplay?

Step 1 - Piano Cue

Wite a short cue of 16 bars for the piano and divide it into a melody-, harmony- and baseline. Use countermelodies, rhythmic acompositions or any other method to enhance the cue to a full theme.

I wrote a minimalistic cue for this part, as I want to use it for the following exercises, where a lot of the harmonic and rhythmic aspects need to be reworked. If you think of implementing a specific method like counterpoint melodies, it would be a good idea to implement them already at this stage.

Exercise 1 - Ambient cue

Use the piano cue and force it into a specific ambient. If you have a lovely sounding cue, set it into the ambient of a dark cavern or a postapocalyptic chasing scene. For ideas on ambient, I love to browse through artworks on Artstation or DeviantArt, as they give me unique ideas with a specific feeling attached.

For this cue, I thought about a darker space ambient, maybe the exploration of an unmanned ship or a gritty place the expedition came to a hold.

I used a lot of digital sound sources and distorted orchestral instruments, which isn’t something I usually use. But it was fun experimenting with those sounds.

Exercise 2 - Emotions

Emotions are the key element in scores and should be the top priority. It is surely one of the most difficult tasks, but it combines orchestration, instrumentation, pacing, and every other aspect to this single goal.

Exercise: use an emotion chart and pick two diffrent moods. At a specific point in your cue, you need to change to mood from one to another. This can be sudden or stretched out and came with dynamic or time signature changes. Don’t be afraid to make a complex structure in the transition, as emotional interpretations and transitions are crucial elements in scoring for film.

For this exercise, I decided to start with a more sinister, hateful variation, and swapped to an adventurous uplifting variation for the second part.

It was really hard to bring something together, as not only the pacing but the use of instruments widely differs. For the darker color I reused some of the soundsources from exercise one, and restructured the chords and textures. For the more uplifting variation I implemented a more classic orchestration approach. The most challenging part was the transition, as it is not only important to adjust the pacing, but to combine both variations somewhat logical.

Exercise 3 - Instrumentation

Divide the cue to the orchestra, but use instruments you usually do not use primarily. For example, the tuba can be used not only as a double for the bass line, its use widely differs from composer to composer. Some use it as a second trombone, others even to accompany the french horns or use it to give the rhythmic section more weight.

The goal is to bring out the highlights of each instrument and use its complete range of articulations.

For Film music ethnic instruments play an important role, as they enhance the ambient and can transform a piece into a nail fitting experience. Use the same piano cue but use ethnic instruments only. This opens up your horizon on wich instrument can perform at wich point the best. You can further divide it into diffrent settings, such as middle eastern instruments or you can as well combine scottish bagpipes with a vietnamese Dan Co.

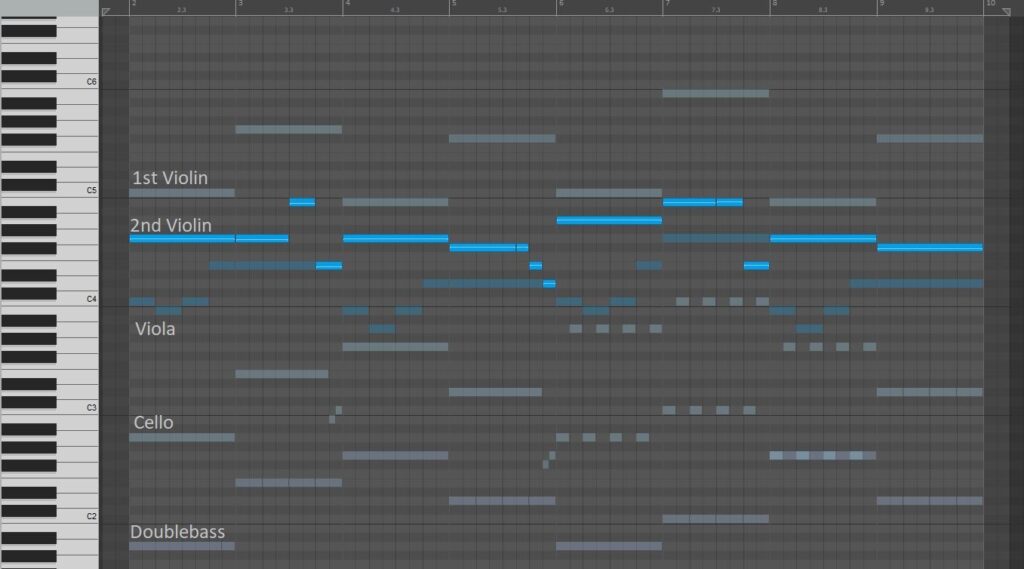

For this exercise, I tried to stick with staccato strings only in order to create a cue more fitting to classical music. I am absolutely not familiar with writing such parts, but I was quite excited with the result.

Many ornamentations and quicker parts for each instrument was a really challenging, but quite funny experience.