Participating in competitions is my number one way to improve writing music for pictures. It not only allows me to get a hand on actual footage to score, but it also allows me to compare my work with a significant amount of other people’s work. I’m not expecting to be among the finalists, but I do compare my submission with the published results of others, as this is a simple yet effective way to open up your horizon for new creative input.

Recently I dived a bit into interviews and articles on composers from diffrent competitions and the jury’s thoughts, as well as how they managed to stick out from the crowd of hundreds of composers.

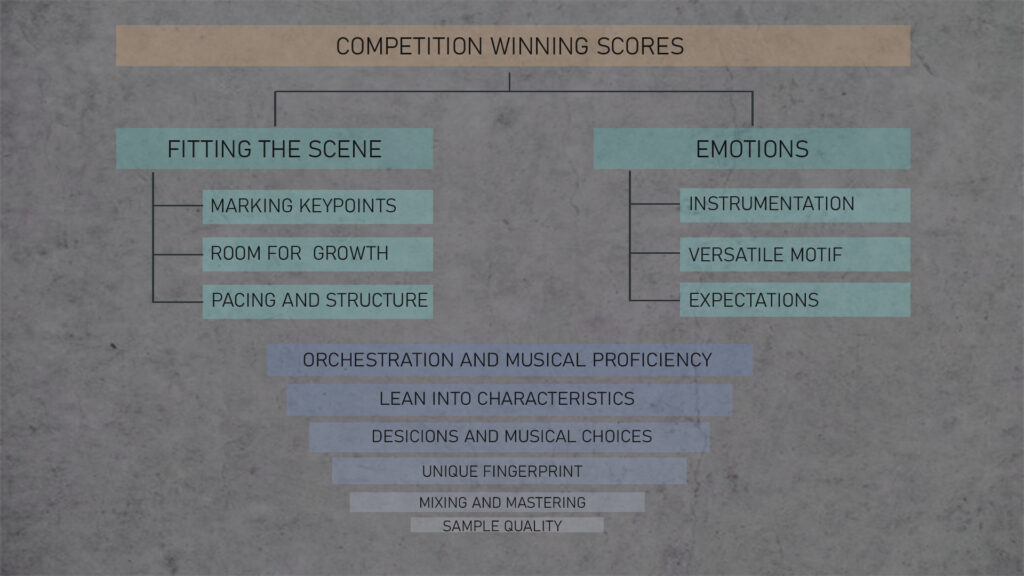

Throughout diffrent interviews, two main reasons stand out on how they managed to win a scoring competition:

Composers achieved a spot-on score in terms of pacing and scene development with a fitting orchestration, as well as stunning orchestration to evoke emotions. They managed to do this by using simple, versatile themes, adding their fingerprint with unique approaches and a clear direction on what story they wanted to tell.

My primary sources for this summary are Jessie Haugen and his breakdown analysis of his winning score for the Indie Film Music Contest, as well as interviews and winner announcements on the Spitfire Film Competitions for Bridgerton and Stargirl, where we can get an in-depth look at the judge’s thoughts on the winning scores of Alexander Debricz (Spitfire Bridgerton Competition) and Chris Hurn (Spitfires Stargirl Competition).

What are the main criteria for selecting scores as winning entries?

As I already showed in this article (tips for competitions), judges tend to focus on a few main aspects of the Score depending on the competition. I think it is needless to say that these scores are spot on in every category, and the composer is well aware of how to transform his ideas into a polished orchestration – but in every discussion between judges, two main aspects stand out:

1. Fitting the Scene

I think most beginning composers, myself included, take a misleading approach to write music for the film. In our imagination, think about the big themes from John Williams, Hans Zimmer, James Horner, etc., that inspire us to go down this road. But in reality, we are not challenged to write the next oscar winning main theme; we are challenged to tell the story of the given footage.

Between the actual screenplay, a lot of subtle information is packed inside, which isn’t clear in the first place but helps to sell the story. The score needs to fit inside the narrative and support this idea without being thrown in the face of the listener. Fitting the scene describes not only the mood or ambiance – we talk about this later – it also needs to fit the pacing, highlight crucial points and blend in the scene to create a harmonizing result.

A few notes i took to outline the fundamentals to fit the scene:

- Short and simple motif

- Marking keypoints

- Give the music space to grow and decent

- Clear structure to let the viewer understand what you want to tell

For competitions, telling the story sometimes becomes even more difficult because it is told in a concise amount of time. Therefore, the main idea needs to be short and straightforward to be versatile enough to fit diffrent aspects of the scenes. Creating a 16-bar melody phrase wouldn’t work in most cases, as the scene switches too quickly to fit the entire story arc in 4 minutes.

It is, therefore, crucial to highlight the significant key points and changes in the footage and give the music the possibility to aim for them and let them stand out. This goes hand in hand with the room music needs to develop and fade out correctly without having a big orchestral theme stretching out from the beginning to the end.

2. Awakening Emotions

Ultimately, creating emotions in music is the main reason to write music for film firsthand. In my latest entry, I forced myself to focus on feelings, but I tended to fall back into my usual habits without giving them the attention they should have.

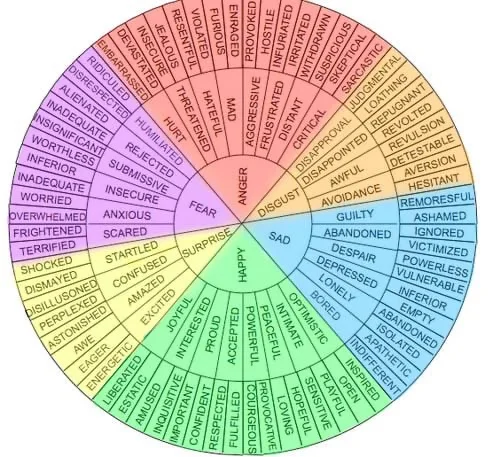

Regarding emotions, the spectrum you can aim for is enormous. If you look at an emotion chart like the one below, it was an eye-opener for me how many possibilities there are. A lot of the time, I have a feeling for the emotion the scene wants to transmit, but I can’t point it what exactly it is.

Using such a chart helps to put a name to it and differentiate between being “scared” and “insecure,” for example. In my opinion, clearly describing the things you want in your score is fundamental to expressing them in music. That’s why many composers don’t talk with their directors about the music when discussing it for a project but focus on the expression of emotions and their meaning for the story.

Transposing the emotion to the music is certainly one of the most difficult crafts a composer for film needs to master. This is one of the main differences to composers of classical music or a songwriter.

This video I found, by Jack Pierce, breaks it down extremely well in a humorous way and is definitely worth watching:

This video shows the impact on diffrent scenes extremely well and makes it understandable why this is a key feature your score should aim for.

So instead of taking a generic approach just to fill the empty space in your track, try to focus on what story the scene really wants to tell and enhance it with a fitting score.

Further important aspects

Unique Fingerpring

A lot of times, taking a unique approach seems to be a good idea. But I think Jessie Haugen said it perfectly when he broke down his winning score for the Indie Film Music Contest. The scene depicted a warm and playful place, and he immediately thought of a lush orchestration featuring piano, strings, and woodwinds. He then thought:” Hey, everybody is writing it in this way, so let’s try something else.“

He then fiddled around with a few ideas, but they didn’t seem to work as well as he liked. So he came back to the piano, strings, and woodwinds. His final statement was:

Lean into characteristics

Reoccurring elements in the footage or characteristic details can be implemented in your score. The critical point here is not to overdo it, as it can lead to “mickey mousing” if every footstep is followed by a tuba, for example. Sometimes characters, especially robots or entities without facial expressions, tend to have other ways of communication, giving you an excellent opportunity to highlight that in your score.

Especially when it comes to objects turned to life or still objects playing an important role in the movie, it might be worth a try to dedicate a part of your score to support the idea of bringing them alive.

Instrumentation

The choice of which instrument to use is highly dependent on the ambient and the emotion we want to create. There are a few common general setups if we think of a specific genre, like action music or calm ambient tracks. Nonetheless, switching up the instrumentation a bit can help you develop the theme further without changing the intention too much.

In Spitfires Bridgerton Competition, a lot of elaborate string constellations could be heard due to the period the show takes place. Alexander Debrizc won the competition and switched the instrumentation up a bit. He used a variety of woodwinds as his main register (for a specific part of the score) but used them in the same way you would with strings, resulting in a score fitting the scene on top but having his own spin.

Less important criteria

To my surprise, many of those categories don’t seem to have that big of an impact, as they never get mentioned – neither by composers nor judges.

Sample quality: It may be obvious that full-time composers have generally said access to higher quality samples, but on no occasion have I found even a hint in a discussion about samples. If we compare the impact of sample quality to the actual judging criteria that get most of the recognition, we can clearly see that these overwhelm such minor aspects

Mixing and Mastering: Of course, a decent production quality should be aimed for, but again: No hints on discussions about mastering or mixing aspects. We need to consider that much of this becomes obsolete if the score is well orchestrated. The only important part of this topic is to make sure the loudness level of your track fits the footage, so dialogues are still easy to understand without the music being hidden in the background.

Instead of racking your brain over mixing and mastering, invest the time polishing your orchestration, as there is no real need for a professional mixing session with modern sound libraries.

Pingback:List of Scoring Competitions 2023 – How to write film music