If you’re thinking about participating in any scoring competition, congratulations! It surely is not everybody’s favorite way to score, but in the end, it is a clear task you are given within a certain amount of time, and it gets you right into the actual craft of writing music for film.

Many questions arise at this stage, and you might be insecure about whether you have the equipment, the skill, or the guts it takes to apply to one of the many competitions. The advice I can give you from my heart is: Do it! Done is better than perfect. Don’t miss out on such unique opportunities to push yourself at the end of your skillset, as this is one of the best ways to improve and have an in-depth experience in this field.

But what do you actually need to know in terms of skills and what technical equipment regarding hardware and software should you possess in order to take action?

A decent knowledge of orchestration and how to evoke emotions is fundamental for competitions. For the judges, your musical ideas and orchestral craftsmanship are the main criteria you need to focus on. Next to this, a few requirements on the side include knowledge of your notation software and the sounds you have at your disposal.

But let’s take a deeper look into these categories and what you actually need in each of them.

Table of Content

- Technical Requirements and why it's not important

- Spotting - Beeing Able to Organize your Structure to Support the Motif of the Footage

- Orchestral Sketching - Using the Given Limitation as Possibility

- Instrumentation - Using the Sounds at your Disposal to Sell the Idea

- Polishing - Giving it the Divine Finish

- Mixing and Mastering - The Realm of Legendary Tales

- Submission - Taking Away the Load from your Shoulders

- Final Thoughts - Requirements on your Personality

Technical Requirements and why it's not Important

Now, this might seem to be the biggest barrier holding you back from participating in a competition. If hundreds or thousands of participants take place, how am I able to deliver a quality that meets the expectations of the judges? Well, the simple answer is the following:

- Sound Quality

Your sound quality is mainly depending on your orchestration. No mixing or mastering engineer can transform a muddy score into a brilliant track. If it lacks the Ooomph you’re looking for – fix it in the orchestration. If the harmonies clash together – fix it in the orchestration. Don’t waste too many thoughts on the mixing and mastering stage, as it is not a magical place where your composition somehow turns into a god-tier level.

Modern sound libraries, even free VSTs like Spitfires BBC Orchestra or Spitfire Labs, have amazing recording quality, where you don’t need to fiddle around in postproduction. Some minor changes can be made, of course, like reverbs or the adjustment of volume in comparison to the movie footage. But focus on the orchestration instead and deliver a beautifully orchestrated piece.

2. Software Requirements

Use whatever you have at your disposal in terms of hard- or software. You can’t hear the difference between a score written in Ableton or a free version of Garage Band. Yes, some equipment would give you more opportunities or make the creation process more accessible, but the software is not writing the score – you are. Be confident in yourself and avoid believing your equipment is a barrier for you to entering competitions

3. Hardware Requirements

For hardware, it is the same principle. I’m not assuming you will record your orchestra in your bedroom, so microphones are not part of this discussion. But even for MIDI-Keyboards, it’s not hearable if you come up with your idea on a cheap plastic MIDI-Keyboard or a handcrafted Grand Piano in an opera hall.

Now that we have checked this part, let’s dive into some topics you actually need in order to deliver an adequate entry:

Spotting - Beeing Able to Organize your Structure to Support the Motif of the Footage

The task is to provide an original soundtrack to a movie, so that should be your priority number one. From my own experience, I can tell you that it is an unbelievably scary experience opening up the video file for the first time, hearing nothing but your own heartbeat, and having the constant thoughts of “What the hell am I supposed to do here?” throughout the entire watch time.

It’s easy to fall into a desperate spiral at this point, blaming the video for being such strange or not fitting a genre you secretly wanted to write.

What you need to be able:

You need to be able to understand what story the movie tries to tell and be able to differentiate between the ambient you see when watching the movie and the emotion you actually need to create in order to support the story.

If you have a chasing scene in your film, I think everybody is going in the same direction of action-driven music. But is this scene intense because of pursuit, or should it be a more heroic approach? Is the character terrified, has he a plan he’s sticking to? Is it a covert action or an open chase through the desert? Is this the actual climax, or should the music lead to a later key point?

My General Spotting Approach:

Before you write your first note or even import the video into your DAW, the general approach is to have a so-called spotting session. This is the first stage in your composing journey and heavily influences the outcome of your track. I usually watch the source material a few times a row to understand what the movie wants to tell me. Usually, even if they are snippets from an existing film or TV Series, they implement a complete story arc in those 4 minutes. Starting from a specific situation, the story develops to a primary key point and then resolves in a final position, differentiating from the start.

I take notes for myself in a random document with the timing of these changes happening. Sometimes it’s easy to align them with a specific action taking place, sometimes, the change is more subtle. It is important not to crumble every single cut into your spreadsheet but to highlight the big important changes.

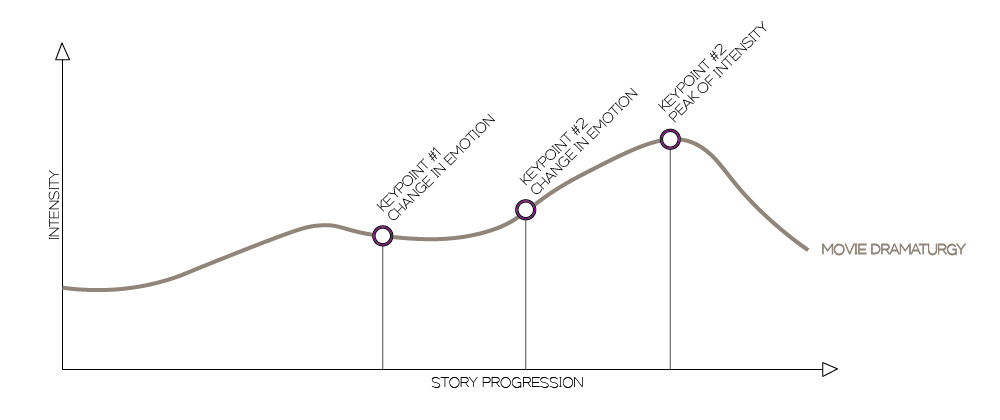

In this chart, I try to give you a more visual understanding: The story of the movie has a variable intensity over its duration. The first step is just about understanding the story arc and figuring out where the peaks and changes in emotions take place.

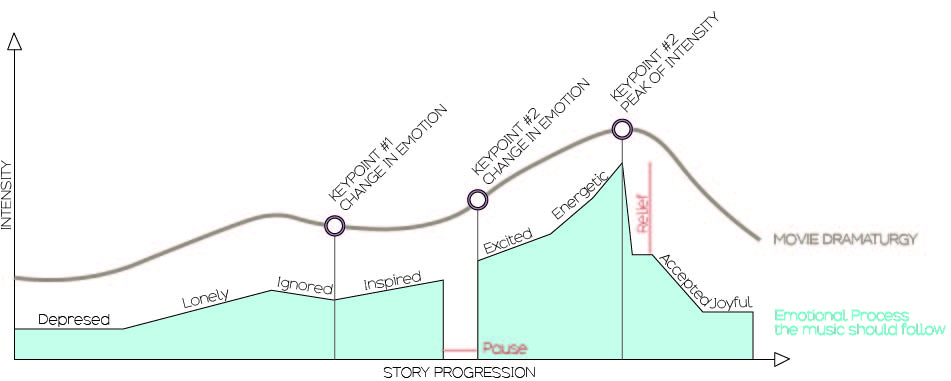

In the next stage, I then think about the emotions I want to evoke. Should the character be scared, happy, or sad? When does this change? Are emotions not visible to the viewer but need to be told to understand the movie properly? With the information of major vital points and designated parts for the emotions, it is now more liberating to decide which type of music I want at which point. Consider your motif’s time to build up and resolve before hitting the next phase.

Once the significant keypoints are clear, I invest time in determining which emotions the score should deliver. In my first scores, I added a keypoint after every scene and wrote from keypoint to keypoint. Now I try to add as less as possible, but with information about the actual emotion, the track should follow. In this way, the score has room and can adjust to the emotional process.

The main critique I found in myself is that I tend not to implement any pauses in music or more subtle passages. I tend to overdo it and actually write music describing the idea but not hitting the exact emotion or timing I want. Don’t be afraid to implement a pause between your cues and give the theme the space it needs to develop, change or resolve.

Orchestral Sketching - Using the Given Limitation as Possibility

What you need to be able:

– Sketching out simple ideas that are versatile enough to follow the story arc

– Recognise recourring details or moments to bring them to life

– Beeing able to create a solid sketch and have the immagination to understand where these sketches lead

My General Sketching Approach:

Now that you have your general outline of the music, where it needs to enter and exit, and which role it has inside the specific scenes, it comes to your first sketching process.

Scoring competitions generally have a short amount of time in which the entire story arc needs to fit in. Therefore quicker scenes and a lot of information are crumbled in a short amount of time. This leads to a way more limiting musical narrative as we simply don’t have the screen time to develop a full musical world around this movie. Try to come up with a short and flexible theme or idea that can quickly transform into diffrent moods.

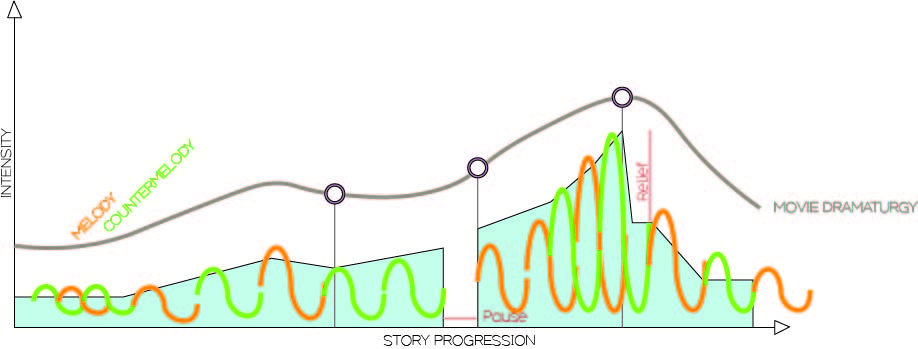

With a simplistic motif, you risk having a repetitive structure inside your score that might become omnipresent and boring. I avoid this by creating a simple melody with an appropriate counter melody and use them as separate lines throughout my score. In this way, I have two melodies to work with, but I can combine them together in order to let a musical dialog happen.

For the orchestral sketch, I try to implement as much information as possible with the melody lines, harmonies, and rhythmic patterns. I spend a long time in this process till I am happy with the result and move to the actual orchestration.

Important Workflow Tip I Learned in the Last Submissions:

In my initial approach, I wrote an entire part of the score before moving on to the next part. Nowadays, I sketch out everything first. I use either a piano or register patches for strings, brass, and woodwinds to mark out my ideas throughout the film. This has two main benefits instead of doing it bit by bit:

- If I want to make any changes, even smaller ones, it is way easier to do so in the sketching phase

- It’s way easier to create a homogenuous piece instead of single stems glued together. The result is in my opinion way better structured and helps to sell the story better.

I spent a lot of time in the sketching phase, as I also write down harmonies, rhythmic patterns, and textures. With such a clear sketch, where the big aspects of the cue are clear, it is way more effective to transcribe them to the orchestra. Take your time, this is one of the best learnings I did in the last years to create a more structured, clearer, and higher quality orchestration at the end.

I often imagine composers as book authors. Authors can be divided into two categories: Planning writers (like J.R.R. Tolkien with The Lord of the Rings, where he even created an entire language prior to writing the book) and discovery writers (like G.R.R Martin with The Song of Ice and Fire, where he just starts writing and doesn’t know himself what’s happening on the next page.) If we use the same principle in composing music, I tend to be a discovery writer if I’m writing standalone music, as there is no limit on where it should take you. But if the task is to write for actual movie footage, the boundaries are quite clear, and the goal is set. Therefore I now use a more planned structure to help me create a score fitting the scene and delivering the emotions at the right time and intensity level.

Instrumentation - Using the Sounds at your Disposal to Sell the Idea

Once your main idea is set, and you have a clear structure in front of you, the next step is to distribute it to the orchestra.

What you need to be able:

- Understanding the principles of dynamic voicing to create a fitting and still variating instrument line-up.

- Will to experiment with diffrent tonal colors to give you the desired result

My General Orchestration Approach:

For Instrumentation, the possibilities are limitless. In my beginning phase, I tended to reuse patterns to distribute the notes among the orchestra purely because they seemed logical or because I was used to doing so. Now I take a more serious approach and try to imagine which instrument carries the emotion the best I want to show. Feel free to experiment with diffrent sounds and constellations. If you allready have a more advanced knowledge of sound creation, you can surely shine with a fitting Soundeffect as a drone or synthesizer pads. For me I use them not that regulary but i try to support my musical idea as best as possible.

Choosing the right instruments is not only a matter of emotion and fitting the scene; it is also crucial to have a bit of variation in it. Otherwise, you would end up with a cue repeating itself over and over, resulting in flat and boring-sounding background noise. You can use your instruments in order to create diffrent amounts of impact, for example, or to underline the emotion. The same melody slowed down on the piano is a more calm approach, while blasting it through a french horn gives you a more aggressive score.

Another thing to consider, even if it is more of a general orchestral scoring principle, is to make a difference between for- and background patterns, to divide them with your instrumental line-up so it is clear which part should stand out for the listener.

Even if it is obvious, ist essential to take into consideration the possibilities of each instrument. Strings, for example, have various articulations to choose from. Staccato notes work really well for more energetic situations, while legato sections have a more lush and open feeling. So if you want to achieve a certain mood or feeling, it’s good to play around with articulations to fit your needs.

Polishing - Giving it the Divine Finish

For the polishing part, the main thing keeping you from rushing it to the end and saying, “That’s enough, it’s done,” is your personal commitment. At this point, your score shouldn’t have any major flaws, but maybe you will find a few single bits that need a bit of rework to blend them better. I personally use this phase to sparkle in a few smaller details, such as flute thrillers or subtle percussion hits

What you need to be able:

- Finding the commitment to bring it to a worthy end

My General Approach:

In my latest submission, I had a problem with a few modular expression points in some instruments. The brass sounded muted down to the bare minimum where they ruffly managed to play, and the flute was just abnormally sharp. As I was pleased with the score itself, I thought about rebalancing the velocities at the end once the track was finished. Polishing out these flaws was such a tremendous amount of work. I ended up rearranging the envelopes for volume and expression for every single stem, resulting in changes of tonal color I didn’t want and a lot of rework to bring them all together again. This was such a demotivating problem that I was in the blink of giving up. That’s why I swore myself never to bring such problems in the ending phase of the scoring process ever again.

Another problem in this phase is that we have already heard the score over a hundred times, and the ear is used to the sound. Some minor flaws get lost and overheard the longer we work in one continuous session. There isn’t much we can do to avoid this apart from taking regular breaks. The best solution would be to leave the score as it is for a couple of days, as after this time, your score isn’t that present in your memory anymore. If you manage to “forget” what your theme sounded like, it is a perfect opportunity to go in with a fresh ear to discover those smaller flaws.

But if you are something like me, I simply don’t have the time to put the track aside, as the deadline usually is around the corner.

Mixing and Mastering - The Realm of Legendary Tales

I know, I know. This is by far the scariest part of the whole process, as there is a high chance that you never got any good at this or even understand in detail what your actually doing. Don’t be afraid; I don’t know either.

I followed a lot of diffrent workflows from diffrent people on YouTube and even took a course on mixing for orchestral music. The result is… barely hearable. For short cues, yes, mixing is a task you can follow to let the single instruments pop out more. But doing so with an entire score is way more difficult. I, therefore, created a workflow for myself that is quite simple but effective, and I am going to show it to you.

What you need to be able:

- Understanding what you actually need to do and executing those steps

- Having a basic understanding of how your mixing plugins work

My General Mixing Approach - short, compact and effective:

First of all, I export every stem separately from the DAW and import them in a new instance. I no longer work with MIDI but with actual audio waves. After reorganizing the project, I do the following:

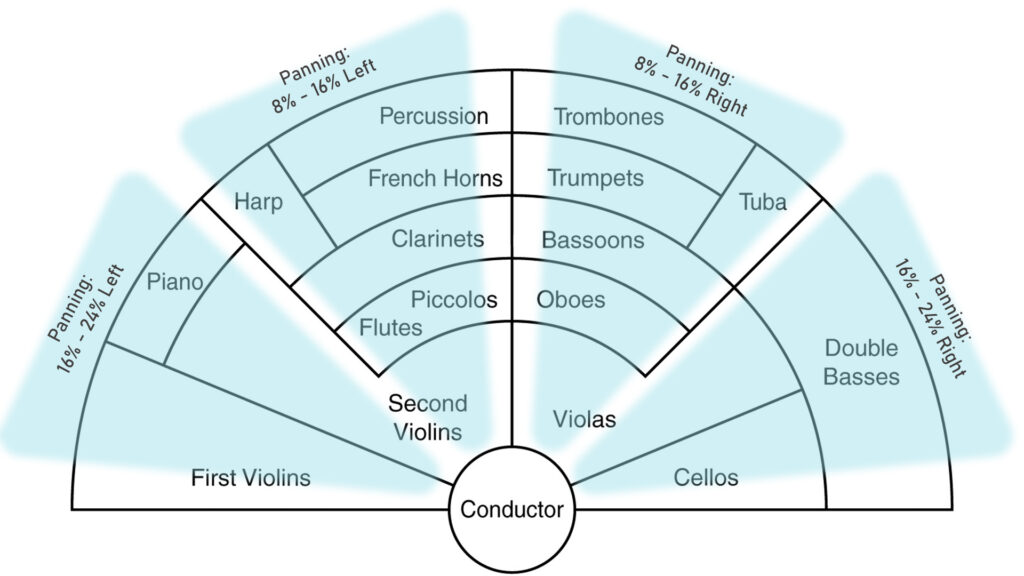

Panning:

Instead of your instruments sitting on top of one another, I spread them out over the stage. This is very easy by adjusting the panning wheel according to the values in the guideline below.

You can immediately hear a big difference in how much broader the sound gets.

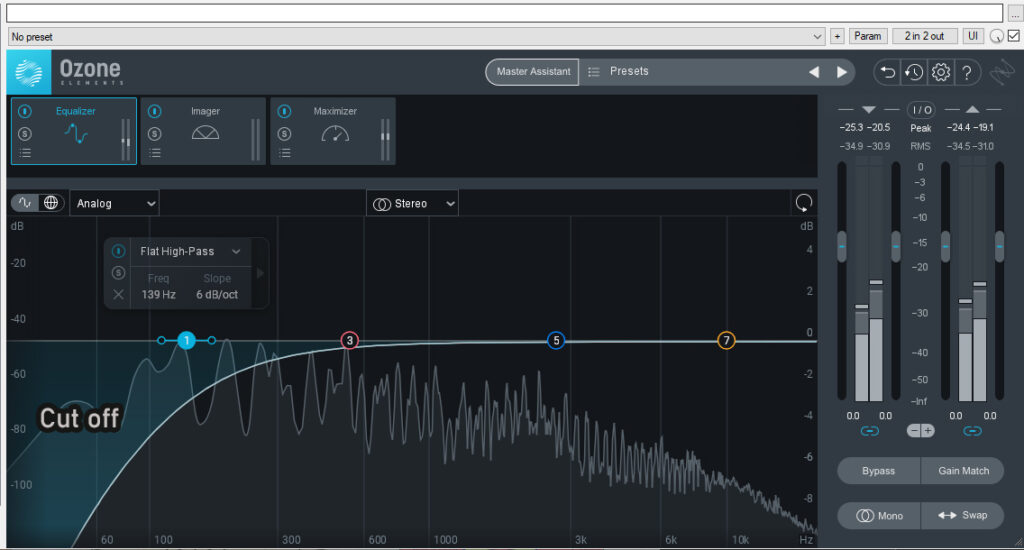

Equalizer:

I use an equalizer to cut off any messy low-frequency background noise. I do this on every instrument singularly and cut out the frequency at around 100 Hz – 150 Hz. I keep it lower on lower-placed instruments such as double basses and the gran cassa, and cut it out a bit higher on higher-pitched instruments.

The reason to do this is to make the orchestra sound clearer, avoid a messy low register section and give each instrument the possibility to lay on a clean sounded with the space they need to distribute their full potential.

Reverb

For me, it always feels like listening to the orchestra from a distance and then stepping inside the recording hall once a reverb is set. Of course, don’t overdo it, but a small amount is not wrong. You can add a single reverb over the entire project – but I tend to add the reverb for each section separately, as I don’t want such an intensity on the percussion usually.

An interesting approach I heard of, but didn’t tried out so far, is to use two reverbs on top of each other. One with a shorter reverb time to bring life to the recording and one more silent, long-stretched reverb to mimic the surrounding. This might lead to a nice experience.

Now your track should be prepared more than sufficient. If you have a good solid orchestration as your base, these steps are just a minor detail. To be honest, sometimes I do them simply to know I have done it. As I am no mixing engineer and we are not recording an actual orchestra, I am sure these steps are enough to have a really solid quality, fulfilling the expectations of the judges.

My General Mastering Approach:

But before we add the track as our final version to the footage, there is one crucial task we need to do prior: Mastering. Don’t be afraid, it’s really easy for our purpose. The goal is to have an exported track that actually brings out the volume we want. If you ever exported a track and it sounded dull and silent, even on full-open speakers, it’s because of the lack of mastering.

To bring your loudness level up, simply export your mixed track into a new instance as a single audio file. The keyword you are looking for is called “maximizer”. A lot of DAWs, such as Reaper in my case, comes with a build in maximizer that does the job. With the maximize, it’s just a play of numbers in the threshold to bring up the general volume without overdrive. And that’s it. Your exported file is ready for the wedding with the source material.

Submission - Taking Away the Load from your Shoulders

How to submit an entry depends on the competition. Sometimes you need to send the mp3 file, sometimes, you need to merge it with the video to an mp4. Maybe you need to upload them to a specific website such as YouTube or sometimes you upload them to the competitions portal.

Take your time, but consider that it might take a while to do it. From your Export to the upload, some things can go wrong and can cost you a lot of time. Simply try not to do it at the last minute, as I don’t want you to risk your submission by missing the deadline due to technical problems.

So be informed on how you need to submit your track, which programs you might need to use to merge video and audio, and so on. I, for example, had the problem that the framerate in the export settings of the video software wasn’t right, resulting in the video being played faster than the music. Another time I realized that I somehow muted an effect instrument, so my playful texture wasn’t even hearable. I realized it after watching the already submitted file again…

So keep in mind that it takes you some time to finish the submission and leave some time to review your work before finally sending it away. Otherwise, your PC works the same as a printer: They sense that you’re under pressure, and you can bet that at some point, something isn’t working as intended.

Final Thoughts - Requirements on your Personality

You absolutely need to:

- Have the spare time to enter and finish the competition in time

- Have the commitment to continue working on it and bringing it to an end

Aside from musical understanding, the most crucial requirement to participate in a scoring competition, where I struggle the most, is finding the time to put in. If you are a professional composer, you might sketch out the entire piece in an hour, but if you are like me, I absolutely need to dedicate two weeks minimum to get a pleasant result. Finding time next to your full-time job, other activities, and hobbies is an important part to take into consideration.

Next to this, the commitment to bring it to an end can sometimes be a bigger task than the score itself. To be honest, I manage to finish ruffly half the competitions I enter. Sometimes I lack focus, sometimes, I can’t figure out what I really want to do with the piece; and sometimes it’s just a lack of commitment to finish it.

I really hope this post can serve as a guideline to approach your next submission. But the most important requirement is: Do it. Don’t spend your time looking up all random stuff on the internet because you think you need a tutorial on every aspect and get distracted. Get comfortable with writing for picture and do it.

Pingback:Practicing Film Scoring: 7 self-critical Approaches – How to write film music